Bibliography

Sources accessed April 05, 2023 - October 30, 2025:

10 Facts About Our Items on Display at the Guildhall, Barnstaple – "Tales From the Archives"(wordpress.com). Barumathena, 2018. https://talesfromthearchives.wordpress.com/2018/11/29/10-facts-about-our-items-on-display-at-the-guildhall-barnstaple/.

Allen, Martin (2004, 2011); Silver production and the money supply in England and Wales, 1086–c. 1500.

Amery et al (1901): "Devon Notes and Queries. A Quarterly Journal devoted to the Local History, Biography and Antiquities of the County of Devon". Vol 1. pp. 173-174. Exeter, J.G. Commin.

AMR Coins (2023): The Henry IV/V divide; a numismatic contention. The Henry IV/V divide | AMR Coins.

Banfield, John (1834); A Guide To Ilfracombe And The Neighbouring Towns: Comprehending A General Sketch Of The History And Objects Most Worthy Of Remark In That Part Of The North Of Devon (1834). Montana. Kessinger Publishing, LLC (22 May 2010).

Barton, D.B. (1989): The Cornish Beam Engine. Exeter. Wheaton Publishers.

Besley, H. (1901); The Route Book of Devon, A Guide for the Stranger and Tourist. Besley, Exeter.

BL Sloane MS 857. Commonwealth inventories of Crown Jewels (1649–1660). British Library, London.

Bone, M., & Stanier, P., 1998, A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Devon, p.40. Multimedia Textbooks (31 Dec. 1998).

British-history.ac.uk/magna-britannia/vol6/ccxcviii-cccvi. Accessed Aug 08, 2023.

British Museum (2023); Henry Ellis & Co: - https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG71523.

British Mining No 57 Memoirs 1996 pp47-69 (nmrs.org.uk) 1996.

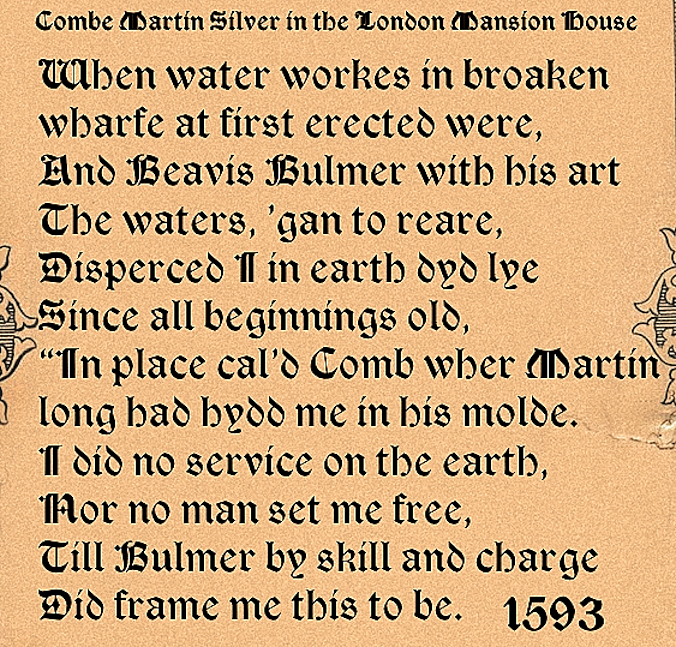

British Numismatic Society (n.d.): Morrieson, H.W. : THE COINAGE OF COOMBE MARTIN, 1647-1648. Accessed March 14, 2024.

Buckley, J. Allen (1992). The Man Engine. The Cornish Mining Industry. Penryn, England: Tor Mark Press. pp. 27–29.

Camden, W. (1607). Britannia, sive florentissimorum regnorum Angliae, Scotiae, Hiberniae, et insularum adiacentium ex intima antiquitate chorographica [a chorographical description of the most flourishing kingdoms of England, Scotland, Ireland, and the adjacent islands from the deepest antiquity]. George Bishop.

Camden, William (transl. 1722): Britannia, or, A chorographical description of Great Britain and Ireland, together with the adjacent islands. Chapter XI Low Dutch Miners in England, The Influence of Low Dutch on the English Vocabulary, E.C. Llewellyn - Digital Library for Dutch Literature (DBNL).

Christie, Peter (n.d.); A North Devon Chronology; The Heritage Album: 175 years in North Devon (1824-1999).

City of London Corporation (2015, October 23): Henry V’s ‘Crystal Sceptre’ displayed at Guildhall Art Gallery. Retrieved from https://news.cityoflondon.gov.uk/henry-vs-crystal-sceptre-displayed-at-guildhall-art-gallery/ .

Claughton, Peter F. « The crown silver mines and the historic landscape in Devon (England) », ArcheoSciences [En ligne], 34 | 2010, mis en ligne le 11 avril 2013, consulté le 05 avril 2023. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/archeosciences/2862 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/archeosciences.2862

Claughton, P., & Smart, C. (2010). The Crown silver mines in Devon: Capital, labour and landscape in the late medieval period. Historical Metallurgy, 44(2), 112–125. https://www.hmsjournal.org/index.php/home/article/view/152.

Claughton, Peter F. (1992): The Combe Martin Mines. Combe Martin Local History Group. Rotapress, Combe Martin.

Claughton, Peter F. (2006): Silver mining and the English Crown: direct management and leasing of the Devon mines. Exeter University. https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fmining-history.info%2Fmhinf%2Fsilver_m.doc.

Claughton, Peter F. (no date): A LIST OF MINES IN NORTH DEVON AND WEST SOMERSET, PETER CLAUGHTON, PUBLISHED BY TONY OLDHAM, RHYCHYDWR, CRYMYCH, PEMBROKESHIRE - Old Combmartin Mine.

Combe Martin History and Heritage Project: "St Peter ad Vincula Church, Combe Martin, North Devon." combemartinvillage.co.uk, 7 Feb. 2025, www.combemartinvillage.co.uk/churches.

Combe Martin Silver Mines online; https://www.combemartinmines.co.uk. Highly recommended.

Cornish Mines and Engines | National Trust Collections.

Combe Martin History and Heritage Project (2023-2025). Silver mining to strawberries | Combe Martin village history. https://www.combemartinvillage.co.uk/silver-mining-to-strawberries.

Devon & Cornwall Notes & Queries, Vol. 1 (1901). Edited by P.F.S. Amery and J. Brooking Rowe. Exeter: J.G. Commin.

Devon and Dartmoor HER: "Mine Tenement, Combe Martin Silver Mine". HER Number MDV31337. 2023.

Devon & Dartmoor Historic Environment Record. (n.d.). Combe Martin Silver Mines. HER Number: MDV12545. Heritage Gateway.

Devon and Dartmoor HER: "Knap Down Mine". HER Number: MDV789. 2023.

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900. Sir Richard Martin (1534-1617). Read more at https://www.woolleyandwallis.co.uk/departments/silver/sv161014/view-lot/43/.

Dodds, B. (2005): Managing Tithes in the Late Middle Ages. The Agricultural History Review, 53(2), pp. 125–140. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40276023

Donald, M.B. (1955): Elizabethan Copper: The History of the Company of Mines Royal 1568-1605. London: Pergamon P.

Dunkerley, T., (2004): Mine Tenement (Correspondence). SDV339645. https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=MDV31337&resourceID=104.

Dyer, Christopher. (2009) Making a Living in the Middle Ages: The People of Britain, 850 - 1520. London: Yale University Press.

"Exmoor Geology &c" (2000). Edwards, R.A. Exmoor Books. Tiverton.

Highfield, J.R.L., Tout, Thomas Frederick. "Edward III". Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 Feb. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-III-king-of-England.

Exeter RAMM: https://rammcollections.org.uk/collections-areas/collection-areas/decorative-arts/ .

Exmoor National Park Historic Environment Record (2023). Search Combe Martin; https://www.exmoorher.co.uk/globalsearch/index?q=combe+martin.

Flynn, C.G., 1999. The decline and end of the lead mining industry in the Northern Pennines, England and Wales. PhD thesis, Durham University. Available at: https://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4569/.

Fowler, Kenneth. "The Battle of Poitiers, 1356: A Reassessment." The English Historical Review, vol. 87, no. 344, 1972, pp. 745–765. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/564236.

Gichard, Michael G. (April 2007): Cornish Engines. Torontocornishassociation.org.

'Gilbert Spoon Saved': www.theexeterdaily.co.uk/news/local-news/ramm-saves-gilbert-spoon.

Girt Down Mine Combe Martin: Exmoor.

Great Exhibition (1851): London, England); Great Britain. Commissioners for the Exhibition of 1851. Official descriptive and illustrated catalogue. London: Spicer Brothers. Wellcome Library.

Hammersley, G. (1973). The Charcoal Iron Industry and its Fuel, 1540-1750. The Economic History Review, 26(4), pp. 593-613.

Harper, Charles G. (1908): The North Devon Coast. London: Chapman and Hall, Ltd. 1908.

Heritage Gateway Devon and Dartmoor HER Number MDV31337: Mine Tenement, Combe Martin Silver Mine.

Hodgett, G. (2006): A Social and Economic History of Medieval Europe. Abingdon. Routledge.

National Park HER MDE8274 (Monument).

Historical Metallurgy: Further work on residues from lead/silver smelting at Combe Martin, North Devon. Nov 10, 2021 - https://hmsjournal.org/index.php/home/article/view/151, accessed Sept. 2022.

HER Exmoor National Park: MDE8262 - West Challacombe Mine (Monument).

Historic Environment Record for Exmoor National Park; www.exmoorher.co.uk/Monument/MDE8262.

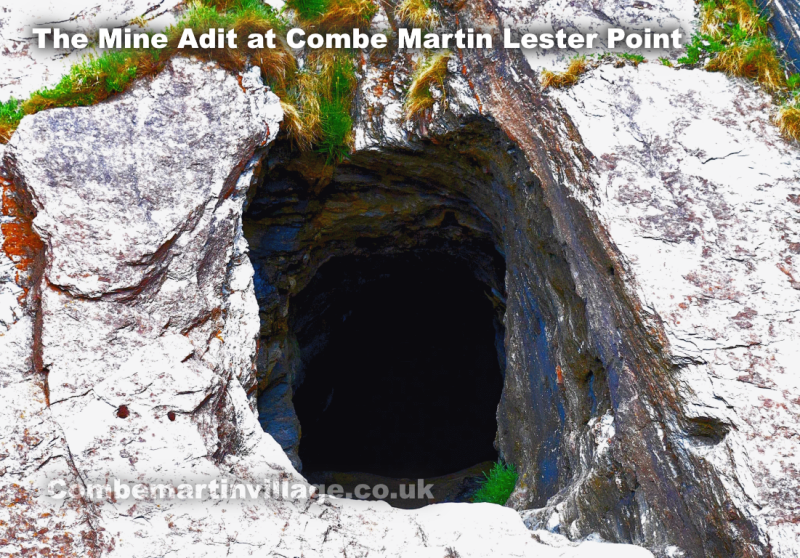

Historic England Research Records Monument Number 614494. Lester Point Adit.

Historic England. "The List Search Results for Combe Martin." Accessed March 8, 202:. https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/results/?search=combe+martin&searchType=NHLE+Simple.

Historic England List Entry Number: 1168925. Engine House and Chimney, Knap Down Silver Mines.

Historic UK. ([Johnson] 2015, March 13). History of the wool trade. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Wool-Trade/.

Homer, Ronald F. (2010) : "Tin, Lead and Pewter," in Blair and Ramsay (eds), 2001.

Irigoin, Alejandra. "The rise and decline of the global silver standard." In S. Battilossi, Y. Cassis, and K. Yago (eds), Handbook of the History of Money and Currency, 383-410. Springer, 2020. Available at: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/119883/1/The_rise_and_decline_of_the_global_silver_standard_LSE_002_.pdf.

Keay, Anna. “Toyes and Trifles: Anna Keay Describes How the Crown Jewels Were Dispersed and Destroyed in 1649, and Then Reconstructed in 1661.” History Today, July 2002. Available online.

Lancaster University (2025): "William Camden." Quakers in the World. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/quakers/notes/camden.html.

Lopez, L. (2017): Chalice. Available at: https://medievallondon.ace.fordham.edu/exhibits/show/medieval-london-objects/chalice.

Lysons, Daniel and Samuel: Magna Britannia: Volume 6, Devonshire (London, 1822). British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/magna-britannia/vol6 [accessed 13 August 2023].

Mate, Mavis (1972): Monetary Policies in England 1272-1307. British Numismatic Society - 1972_BNJ_41_8.pdf (britnumsoc.org).

Malynes, Gerard. "The Ancient Law-Merchant." Early English Books 1641-1700, 1686. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/bim_early-english-books-1641-1700_the-ancient-law-merchant_malynes-gerard_1686/page/184/mode/2up.

Malynes, Gerard. Consuetudo, vel, Lex Mercatoria: or, The Ancient Law-Merchant. London: Printed by Adam Islip, 1622/1628.

Marsden, Christopher. "The Great Exhibition of 1851." The Gazette, https://www.thegazette.co.uk/all-notices/content/100717.

Mercy Madge (n.d.): Rare antique Victorian English silver bow. Retrieved from https://mercymadge.com/products/rare-antique-victorian-english-silver-bow-38593.

Merrington, A. (2023): Exeter University. "Evidence of Roman mining in Cornwall". https://news.exeter.ac.uk/faculty-of-humanities-arts-and-social-sciences/great-british-dig-and-university-archaeologist-find-first-excavated-evidence-of-roman-mining-in-cornwall/.

Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York 2004), Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art: The Phoenicians (1500–300 B.C.).

Milners Solicitors (2023): Legal History: 7 Early Landmark Court Cases. Available at https://www.milnerslaw.co.uk/legal-history-7-early-landmark-court-cases/.

Mindat.org: Silver-bearing Galena. Accessed Aug 08, 2023.

Mindat.org contributors (2024). Bere Alston Mines, Bere Ferrers, West Devon, Devon, England, UK. Retrieved from https://www.mindat.org/loc-1508.html.

Mindat.org (2024): Glossary of Mineralogical Terms, https://www.mindat.org/glossary.php?frm_id=glos&cform_is_valid=1&s=Adit&submit_glos=Search+Glossary.

Navsbooks (Wordpress) October 29, 2018: Some Cornish Mining Terms. https://navsbooks.wordpress.com/2018/10/29/some-cornish-mining-terms/ .

NDAS: Newsletter 2, Issue 9, Spring 2005. Http://www.ndas.org.uk/NDAS%20nl%209.pdf.

Northcote, Rosalind. Devon, Its Moorlands, Streams and Coasts. Illustrated by Frederick J. Widgery. Project Gutenberg, September 1, 2007. E-book #22485. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22485/22485-h/22485-h.htm.

Northern Mine Research Society (2024): "Devon and Cornwall Mines". https://nmrs.org.uk/mines-map/metal/cornwall-devon-mines/.

Office of the State Geologist (2025). "Zinc and Lead." Arkansas Geological Survey. https://www.geology.arkansas.gov/minerals/metallic/zinc-and-lead.html.

Page, John L.W. (1895); The coasts of Devon and Lundy Island. Accessed Aug 27, 2023.

Paynter, Claughton and Dunkerley (2021 [2010]): Further work on residues from lead/silver smelting at Combe Martin, North Devon. Historical Metallurgy 44 (2) 2010 I 104 -111. Available online.

Pengelly, W. (1879). Transcript of Combe Martin. In II. Kingsley, Rev. Canon (Ed.), Notes on Slips connected with Devonshire (Pt III). Trans. Devon Assoc, Vol XI, pp. 360-363. Retrieved from GENUKI.

Postan, M.M. (1974): The medieval economy and society. Harmondsworth. Penguin Books.

Potter, W.J.W. (1959-1961): The Silver Coinage of Richard II, Henry IV, and Henry V.

Presland, John (1917): Lynton and Lynmouth: A Pageant of Cliff and Moorland. London. Chatto & Windus (Penguin Books).

Prestwich, Michael. "The Battle of Crécy, 1346." The English Historical Review, vol. 92, no. 365, 1977, pp. 333–345. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/566720.

Prestwich, Michael (1969): Edward I's Monetary Policies and Their Consequences. The Economic History Review

Vol. 22, No. 3 (Dec., 1969), pp. 406-416 (11 pages). Published by Wiley.

Prestwich, Michael (2005). Plantagenet England: 1225-1360. Oxford University Press.

Rippon, S., Claughton, P. and Smart C. 2009: Mining in a Medieval Landscape: the royal silver mines of the Tamar Valley. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. https://www.exeter.ac.uk/research/projects/archaeology/silvermining/.

Science Museum Group (n.d.) Cornish Pumping Engine Model built by Harvey & Co. Available at: https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8621384/cornish-pumping-engine-model-built-by-harvey-co (Accessed: 7 June 2025).

Shackleford, K. W. (n.d.) Combe Martin Mines. Available at: https://www.genealogy.com/ftm/s/h/a/Kendrick-W-Shackleford/FILE/0039page.html (Accessed: 31 August 2024).

Snell, F.J. (1906): North Devon. London. Adam and Charles Black.

Stubbs, W. (Ed.). (1882): The Annales Londonienses; Chronicles of the Reigns of Edward I and Edward II. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

The Crown Estate (n.d.): Commercial exploration of Mines Royal. Available at: https://www.thecrownestate.co.uk/our-business/land/commercial-exploration-of-mines-royal.

The National Archives (TNA), E 101/263/12. Account of mines at Combe Martin (Devon), 33 and 34 Edward III. King’s Remembrancer: Accounts Various, MINES subseries, 1359–1360.

The National Archives. (n.d.): The Battle of Agincourt. Retrieved from https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/agincourt/.

Tylecote, R.F. (2002): A History of Metallurgy. 2nd edition. London. Institute of Materials. Maney Publishing.

Warburton, M. (2001). Industrial Archaeology - A Guided Walk Through Combe Martin's Past. Devon & Dartmoor HER SDV81878.

Ward Lock (1938): A Pictorial and Descriptive Guide to Bideford, Clovelly, Hartland, Barnstaple, Ilfracombe and North-West Devon. Special Section for Motorists. Eleventh Edition, revised. London. Ward Lock and Co.

"Why are lead and zinc commonly found together?". Chemistry Stack Exchange, May 18, 2020.

Wilson, John M. (1871): The Imperial Gazetteer of England & Wales .London. A. Fullarton & Co.

White, William (1878-79), Gazetteer of the County of Devon etc. London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Co.

Worth, R.N. (1895): A History of Devonshire. London : Elliot Stock, 62, Paternoster Row, E.C.

![Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story] Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story]](https://primary.jwwb.nl/public/i/j/k/temp-bexcyixkrnloblaipglr/cmvhp-logo-01-june-2025-high.png?enable-io=true&enable=upscale&height=70)

![Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story] Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story]](https://primary.jwwb.nl/public/i/j/k/temp-bexcyixkrnloblaipglr/cmvhp-logo-01-june-2025-high.png?enable-io=true&width=100)