Mining in Devon and Cornwall (Overview)

A Historical Survey of Silver, Lead, and Metalliferous Mining

Tags

A secondary source synthesis, updated for accessibility, accuracy & clarity.

By the Combe Martin Village History Project (CMVHP) ©2023-2026

Originally posted in November 2023 | Last modified on January 24, 2026.

Related articles: Early Silver Mining in Combe Martin | Geology of Combe Martin

Key Takeaways

- Article Scope: Localised, well-referenced history of silver mining in Devon and Cornwall with emphasis on the North Devon coastal settlements of Combe Martin, Berrynarbor and Watermouth.

- Ore and Geology: Galena (a lead ore that commonly carries silver) and argentiferous veins supported sustained extraction and on-site processing.

- Regional Context: These workings sit within the south‑west mining tradition, linked to Dartmoor’s long history of copper and silver‑lead extraction.

- Techniques: Evidence spans surface working to Roman and medieval underground methods, including shaft sinking, adits and local ore processing and smelting.

- Economic Impact: Devon silver contributed to provincial mints and state finance, funded military expenditure in the medieval period, and the lead/silver industry later declined under foreign competition and rising costs by the mid‑19th century.

- Boom and Bust: The local silver mining era, while central to Combe Martin's identity, was characterised by boom-and-bust cycles until the industry finally ceased around 1880 due to persistent flooding, rising costs, and cheaper foreign competition (CMVHP, 2023–2025).

- Transition: Combe Martin switched to its soil from the mid-19th century, eventually becoming renowned across the British Empire for its market gardening industry (especially for exceptional strawberries) and tourism (Early Silver Mining in Combe Martin [CMVHP, 2023–2025]).

- Crown Policy: Records show that the Crown abandoned the Combe Martin Royal silver mines quite quickly after its 1292 opening, focusing more heavily on the Bere Ferrers mine in South Devon. The Combe Martin 'Mines Royal' were leased, and were worked successfully by agents.

- Archaeology: Fieldwork and surveys reveal Roman-period industrial mining, medieval reworking of older deposits and surviving landscape traces such as spoil heaps and slag.

- Evidence for Roman Silver Mining: While Romans mined lead and argentiferous galena in Britain, direct proof of Roman silver extraction at Combe Martin is lacking.

What is Dumnonia

Dumnonia denotes the early medieval south‑west territory roughly covering modern Devon, Cornwall and parts of Somerset and Dorset. It remained a distinct cultural and political region after Roman rule, maintained coastal trade connections and overlies exceptionally rich mineral geology, explaining persistent local mining from the Iron Age through the medieval period.

Related articles: Industrial History of Combe Martin↗ | Combe Martin Ores and Smelting↗

Abstract

This synthesis by lead writer J.P. offers a concise overview of the mining history of Devon and Cornwall — the ancient region of Dumnonia — from the Iron Age to the medieval period. Renowned for some of the richest mineral deposits in Britain, the West Country supplied silver, lead, copper, tin, and later arsenic.

According to recent studies, Britain’s long‑distance tin trade shaped Bronze Age economies across Europe and the Mediterranean.

The article highlights key mining centres at Combe Martin, Berrynarbor, and Watermouth, situating them within the wider metalliferous traditions of Dartmoor. It explains the importance of galena (lead‑sulphide ore) as a source of silver, and outlines Roman and later underground techniques such as shaft sinking.

Economic significance is also addressed, including the Crown’s reliance on Devon’s silver revenues and the local silver mining industry’s eventual decline in the nineteenth century. A full bibliography is provided. Non‑commercial sharing with attribution is permitted; please do not edit or adapt the content.

Information for Visitors

Today, visitors can still trace and visit this legacy in the landscape — from the Combe Martin Mine Tenement and spoil heaps at Bowhay Lane, to the Iron Age hillfort at Newberry Castle and the medieval silver‑lead workings at Bere Ferrers in the Tamar Valley. Together with Combe Martin's geology, each archaeological site offers tangible reminders of Britain’s rich mining heritage.

Miners once searched for valuable ores and minerals all over a self-sustaining and innovative coastal parish, rich in Geology. Combe Martin's wealth of minerals and ores supported a cluster of nine quarries and multi-industrial activities, long before the Industrial Revolution during 1760–1840.

Combe Martin Silver Mining

Combe Martin is rich in Geology and history. Galena, a principal ore of lead ['led'], often bears silver (Mindat.org, 2025). Besides Combe Martin's eastern Mine Tenement on Bowhay Lane EX34 0JN: the Exmoor Historic Environment Record lists silver-lead workings around Berrynarbor and Watermouth between Combe Martin and Ilfracombe (North Devon).

The oldest of these workings is situated near the Iron Age univallate hillfort - 'Newberry Castle' - on Newberry Hill (Exmoor HER No. MDV12550), North Devon. A mile away from Berrynarbor, the site lies between Combe Martin and Berrynarbor beside the A399, at OS National Grid reference SS 571 470.

Limitations and Transition

Claims of a lost silver/lead ['led'] mine at Parracombe on Exmoor, just east of Combe Martin, proved to be erroneous (Exmoor Heritage Environment Record MDE20114).

Unlike Combe Martin’s verified silver mines, Parracombe’s site showed no signs of sustained mining activity.

The local silver mining era, while central to Combe Martin's identity, was characterised by boom-and-bust cycles until the industry finally ceased around 1880 due to persistent flooding, rising costs, and cheaper foreign competition (CMVHP, 2023-2025).

The decline also aligns with the mature phase of industrialisation in the 1840s. And with the wider shift toward large‑scale, steam‑powered mining that rendered small, labour‑intensive silver workings including Combe Martin economically obsolete (Paynter, Claughton & Dunkerley [Historical Metallurgy], 2010).

Combe Martin subsequently adapted, eventually becoming well-known for its market gardening (especially strawberries) and tourism (Early Silver Mining in Combe Martin [CMVHP, 2023-2025]).

Primary Evidence for Roman Silver Mining in Combe Martin

Physical evidence for Roman-era mining at Combe Martin centres on the discovery of 4th-century pottery—including coarsewares or sherds (everyday Roman pottery) and a Roman iron stylus—uncovered during excavations (Dunkerley, 2005).

Found within stratified layers of mining waste and "deads," these artifacts provide a "smoking gun" that dates local activity and a Roman presence to the late Roman period, approximately 301–400 AD (Dunkerley & Claughton, 2006).

This archaeological evidence is directly linked to visible landscape traces of opencast mining or "trenching." In these areas, the top layers of earth were scraped away to reach the argentiferous galena (silver-bearing lead ore) beneath.

While the ground clearly shows these ancient surface excavations, direct proof of a Roman-era silver smelting furnace in Combe Martin remains unconfirmed in the current archaeological record (Claughton, P., 2007).

Despite the lack of a confirmed furnace, the site was almost certainly a functional node in the Roman Empire's regional mining landscape. The Romans were intensely interested in British lead-ore for its silver content, most notably at the Mendip Hills in Somerset.

As historian Peter Claughton notes, the high silver yield of Combe Martin ore would have made it a high-priority resource for the Roman administration to control for imperial finance and coinage.

Summary of Sources

Dunkerley, T. & Claughton, P. (2006). "The High Medieval Silver-Lead Mines of Combe Martin: An Archaeological Survey." Journal of the Historical Metallurgy Society. (While focused on Medieval eras, this paper provides the context for the Roman sub-strata).

Claughton, P. (2007). The Crown Silver Mines and the Historic Mining Landscape in Devon. University of Exeter. (The definitive academic thesis on the region's mineral history).

Devon Historic Environment Record (HER). Reference: MDV1051 – "Evidence of Roman mining at Combe Martin."

The British Iron Age

The British Iron Age is the prehistoric period conventionally dated from c. 800 BC with the introduction of iron working, concluding in AD 43 with the Roman conquest of southern Britain (Cunliffe, Barry W., 1978).

However, in Scotland and Ireland, where Roman occupation was absent or limited, Iron Age cultural traditions and technologies persisted well into the early medieval period, c. 5th century AD (Scottish Archaeological Research Framework, n.d., The Influence of Rome).

Native architecture and La Tène-style artifacts (Celtic people's La Tène period, c. 450 BCE – 1st century BCE) continued alongside early Christian influences (Alcock, Leslie, 2003, Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850).

Berrynarbor Iron Age Fort

Historic England Research Records: The Castle/Newberry Camp

Hob Uid: record number 34091

Location: North Devon | Berrynarbor | Grid Ref: SS5717047090

A small but typical Iron Age fort at the eastern end of Newberry ridge: the west side of the Newberry Castle or Newberry Camp archaeological site is fortified with a bank, and an outer ditch (Historic England Hob Uid: 34091).

A hillfort is a settlement located on a hilltop that has been fortified for defence. Across Britain and Ireland, there are more than 4,000 identified or potential hillforts, with Scotland home to over 40% of them, totalling 1,695 (AOC Archaeology Group, 2025).

The hill-slope earthwork, discrete from a cliff-edge site, encompasses approximately 0.4 hectares, which is equivalent to about 4,000 square meters or roughly 0.99 acres. It overlooks the harbour of Sandy Bay in Combe Martin Bay (Heritage Gateway, Historic England).

No remnants of the earthworks are visible, though a faint outline of a ditch appears in low light. A geophysical survey conducted in 1999 detected the enclosure ditch, along with a second ditch and potential signs of activity within the interior (Walls, T., 2000).

Recommended article: Berrynarbor News Edition 199 - August 2022>

Silver in Devon and Cornwall

Parts of Devon and Cornwall - archaic Dumnonia - contained some of the richest mineral deposits in the world (Newcastle University, June 2023). Southern Devon's Dartmoor heritage is intertwined with mining activities, particularly the extraction of copper and silver-lead.

Mary Tavy on Dartmoor’s western boundary was renowned for these mineral deposits. The mines in this region were active from the 18th century to the 20th century, evidencing Dartmoor's long industrial mining history (Devon & Dartmoor HER MDV4185: Wheal Friendship Mine, Mary Tavy).

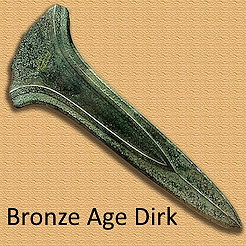

The British Geological Survey (BGS, 2023) states that mining for Lead ['Led'] ore and argentiferous galena (silver) has a long history, dating back to the Iron Age.

Silver is rarely found as a single native element. Historically, many Lead-mines around the world have produced significant quantities of silver as a by-product; and production remains constant today.

Caveat on Roman-Era Silver Extraction at Combe Martin

While archaeological evidence indicates that Combe Martin, a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) was part of the broader Roman mining landscape in Devon and Cornwall, the specific extraction of silver at this location remains an area of ongoing research.

Although it is well-documented that the Romans engaged in mining activities for various ores, including lead and argentiferous galena, definitive proof of significant Roman silver extraction at Combe Martin is still lacking.

Current findings suggest that while the region was rich in mineral deposits, the extent and scale of silver production specifically at Combe Martin require further validation through targeted archaeological investigations, and detailed excavation reports.

Until more conclusive evidence emerges, claims regarding Roman silver extraction should be viewed with caution, emphasising the need for continued scholarly research and archaeological scrutiny.

Ancient to Modern Age Silver Mining

The Phoenicians: Mediterranean Trade and Silver Mining

The Phoenicians, a maritime people descending from the broader Canaanite civilisation, were known for their extensive trade networks and exploration across the ancient world (Markoe, G., 2000). The Phoenicians were not an empire but a commercial confederation of Semitic-speaking city-states (ibid).

The ancient Phoenician civilisation flourished between 1550 and 300 B.C.E (National Geographic, 2025), from the Late Bronze Age through to the Early Iron Age in Europe and the Mediterranean (c. 1500 B.C.E. to c. 300 B.C.E).

Remarkable seafarers, their trade networks often extended beyond the strict boundaries of the Mediterranean. However, arguments for direct contact between Phoenicians and Britain is still debated.

Western Mediterranean Operations

Driven primarily by a quest for silver and tin, the Phoenicians expanded westward to the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal) during the 9th century BCE. To facilitate this trade, they developed significant operations to mine lead-silver ore in the region. Their key western mining zones and colonies were primarily located in the Iberian Peninsula and Sardinia.

From these western outposts, the Phoenicians tapped into even more distant Atlantic networks, reaching the tin-rich shores of Northern Europe.

Britain’s Bronze Age Tin Trade: Archaeological Science and Classical Testimony

Archaeological science and ancient literary testimony increasingly converge to demonstrate that Britain—particularly the tin‑bearing regions of Cornwall and Devon—played a significant role in supplying tin to Mediterranean societies during the Bronze Age (spanning roughly from the fourth to the early first millennium BC).

The tin evidence relates to Bronze Age trade, not to Combe Martin specifically. Recent isotopic and trace‑element analyses of tin ingots recovered from Late Bronze Age shipwrecks off Haifa, Israel, have shown that the metal originated in southwest Britain, indicating long‑distance exchange networks extending over 4,000 km by the thirteenth century BCE (Berger et al. 2025; Haaretz 2025).

Parallel analyses of ingots from the Rochelongue shipwreck off southern France (c. 600 BCE) likewise match geological signatures from Cornwall and Devon, reinforcing the continuity of Atlantic–Mediterranean tin traffic into the early Iron Age (Berger et al. 2025).

These scientific findings align closely with classical accounts. Strabo, writing in the early first century CE, described the tin resources of Britain and their integration into wider Mediterranean trade routes (Geographica IV.5.2).

Diodorus Siculus, drawing on earlier writers such as Posidonius, recorded that tin was extracted in Britain and transported to the Continent, where it entered wider Mediterranean trade networks.

Although Diodorus does not name the Phoenicians directly, his account aligns with other classical sources that associate this long‑distance commerce with Phoenician maritime traders (Bibliotheca historica V.22).

Although no archaeological evidence suggests that Phoenicians mined tin directly in Cornwall, the convergence of isotopic provenance studies, shipwreck evidence, and ancient literary testimony strongly supports the conclusion that Phoenician traders reached Britain to acquire tin, which was subsequently redistributed throughout the Mediterranean to sustain bronze production.

Plain English Summary: Tin Trade in Ancient Times

Recent scientific tests on ancient tin ingots found in shipwrecks near Israel and France show that the metal came from southwest Britain, including Cornwall and Devon. This means that, over 3,000 years ago, people were trading tin across thousands of kilometres, linking Britain to the Mediterranean.

Greek and Roman writers also described Britain’s tin and how it entered long‑distance trade routes through skilled seafaring merchants. Although they don’t name the Phoenicians directly in these passages: other ancient sources and modern research suggest that Phoenician traders were involved in acquiring and redistributing British tin, across the Mediterranean, for bronze production.

In short: long before Roman times, Britain’s tin was valuable, widely traded, and part of a vast international network. Britain’s long-distance tin trade transformed the Bronze Age across Europe and the Mediterranean (Durham University, 2025).

Bibliography

Primary Sources

-

Diodorus Siculus [of Sicily]. Bibliotheca historica. Book V.

-

Strabo. Geographica. Book IV.

Secondary Sources

-

Berger, Daniel, Alan Williams, Benjamin W. Roberts, et al. 2025. “Isotopic and Chemical Provenance of Late Bronze Age Tin Ingots from the Eastern Mediterranean and Atlantic Europe.” Journal of Archaeological Science (forthcoming).

-

Durham University (2025). Britain’s long-distance tin trade transformed the Bronze Age across Europe and the Mediterranean.

-

Haaretz. 2025. “Ancient Tin Ingots Found off Israel’s Coast Came from England, Researchers Say.” Groundbreaking study: Ancient tin ingots found in Israel were mined in England | The Times of Israel (2019).

-

Roberts, Benjamin W., and Christopher P. Thornton. 2014. Archaeometallurgy in Global Perspective: Methods and Syntheses. New York: Springer.

-

Penhallurick, R. D. 1986. Tin in Antiquity: Its Mining and Trade Throughout the Ancient World with Particular Reference to Cornwall. London: Institute of Metals.

-

Tylecote, R. F. 1992. A History of Metallurgy. 2nd ed. London: Institute of Materials.

The Question of Britain and Silver

Cicero's Claim

The Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BCE) asserted that there was "not an ounce of silver in Britain" (Cicero to Atticus; in Tyrrell, 1915, Letter No. CXLIV). Cicero’s remark is generally interpreted as political hyperbole rather than a literal geological claim.

However, archaeological evidence contradicts this claim. Lead ingots, or "pigs," stamped with the names of Roman emperors, some dating back to the first century CE, attest to the significant and immediate Roman interest in the extraction and utilisation of silver in Britain (Tylecote, R.F. [2009], Roman Lead Working in Britain).

The Combe Martin Phoenician Legend

Older guidebooks about Combe Martin claimed that the Phoenicians took ores, including tin and silver, from the area. The Phoenician Steps exist in Combe Martin today. However, there are no available records to substantiate these stories.

The steps are a relatively modern romantic attribution, rather than proof of genuine ancient trade contact. Furthermore, despite their extensive voyages there is scant evidence that the Phoenicians ever travelled as far as North Devon (Markoe, Glenn, Phoenicians, 2000).

However, more recent archaeological science has demonstrated that tin from both Cornwall and Devon did enter Mediterranean trade networks, during the Bronze Age. Isotopic analyses trace ingots found in shipwrecks off Israel and France, back to southwest Britain (Berger et al., 2025, From Land’s End to the Levant...).

New studies in 2025 suggest that while local traditions about Phoenician presence in Combe Martin are unsubstantiated, the broader West Country region was indeed connected to long-distance exchange systems, in which Phoenician merchants were key intermediaries.

The Rise and Fall of British Lead and Silver Mining

The British Geological Survey (BGS, 2023) states that the majority of historic mining activities in Britain occurred during specific time periods. Lead-ore and silver mining featured prominently in Britain during the Roman occupation, AD 43 to around AD 410.

Large-scale industrial mining for lead-ore continued well into the 19th century (British Geological Survey [BGS], 2023). In the 18th and 19th centuries, Britain again became a global leader in lead production. Mechanisation such as water wheels improved efficiency, yet mining remained labour-intensive.

The Yorkshire Dales were prominent for lead mining during this period, though competition from cheaper imports led to the decline of British mines by the early 20th century.

Colin George Flynn's thesis (1999) highlights that by 1865, the United Kingdom started importing more lead metal than it exported.

The domestic lead mining industry had been reduced by half. Once a driving force of the Industrial Revolution, this industry became an early example of industrial decline (Flynn, PhD Thesis, Durham University,The decline and end of the lead mining industry...(1999).

Modern statistics report the estimated global production of silver as 26,000 metric tons in 2022 (Statista.com, 2023). This is equal to approximately 835.92 million ounces at about £18 per ounce, amounting to a total value of around £15.05 billion in 2022.

Local Evidence of Roman Occupation

Local archaeology suggests that North Devon including Combe Martin was an important part of the Roman economy. Ancient relics found in Combe Martin include pottery dating to the 4th century, along with traces of Roman strip mining or dragline excavation in the eastern part of Combe Martin (Moore, J. H., online 2023: ROMANS; c50 AD to 410 AD).

Conclusive archaeological proof of silver extraction (as opposed to just lead mining or general metal prospecting) at Combe Martin specifically during the Roman period is still a subject of ongoing research. However, the evidence for Roman interest in the mineral wealth of Devon and Cornwall is strong (Claughton & Smart 2010, 20–22).

The Romans employed a range of mining methods including shaft sinking and underground mining. With these methods the Romans were able to uncover a range of ores and metals for use in their empire (Hirt, A.M., 2010).

The Beacon at Martinhoe near Combe Martin was a Roman coastal fortlet established in the 1st century AD. This fortlet consisted of an inner square enclosure surrounded by a sub-circular outer enclosure.

During the 1960s, archaeological excavations uncovered the foundations of three building ranges within the Martinhoe fortlet (Exmoor National Park: MDE1020).

There is another Roman settlement located at Old Burrow near County Gate. The site features a square enclosure measuring approximately 44 meters across, situated within a larger sub-circular enclosure that spans about 85 meters (Exmoor National Park HER MDE1223).

Archaeological excavations conducted in 1911 and the 1960s indicate that Old Burrow was a Roman signal station, occupied for a short period in the middle of the 1st Century AD (ibid).

Recommended article: an antiquarian history of Combe Martin incl. the mines>

Medieval Devon and Cornwall

The Devon silver mines, including Combe Martin's 'Mines Royal', contributed substantially to provincial mints in England and Wales throughout the late medieval period. Covering 20,000 hectares across Cornwall and West Devon: the Cornwall and West Devon landscape is a Mining World Heritage Site (UNESCO, 2023).

Claughton and Rondelez (2013) wrote that the abundant surface silver deposits in the dales and moors of England's North Pennines - the present National Parks of the Yorkshire Dales and Northumberland - were 'exhausted in the late 12th century'.

Allegedly, England then relied on mineral resources from mainland Europe (ibid, Early Silver Mining in Western Europe). Historically, northern England's wealth of coal and metals drove industrial developments in the region.

Northern England contributed to the UK's national wealth (British Geological Survey, 2010). Yet recent archaeological evidence indicates that the Romans mined for precious metals in Devon and Cornwall, shortly after their arrival in Britain (Merrington, A., June 2023).

The Devon Great Consols [Copper] Mine

-

The Devon Great Consols Mine is part of the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape, recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site (Cornish Mining World Heritage Site, 2011).

-

Founded in 1844: Investors leased the land from the Duke of Bedford and quickly struck a rich copper lode.

-

This was one of the largest and most productive copper mines in Europe.

-

Its history illustrates the boom‑and‑bust cycles of mining in Britain: rapid growth, immense wealth, followed by decline as ore quality fell and foreign competition increased.

-

Today, remnants of the mine and arsenic works remain visible in the Tamar Valley, serving as industrial heritage landmarks.

Medieval Silver Production in Devon and Cornwall

The thirteenth-century English monarchy invoked prerogative powers with rights and profits over silver-bearing ores and opened up mines in Devon including Combe Martin. In practice: unprecedented Royal powers, and direct management over England's silver production, did not require consent from the Commons or Lords (Claughton, P., 2007).

According to Martin Allen (2010): around the year 1200 AD, mines in Wales provided a modest quantity of silver to nearby mints. And silver from Devon contributed to the national mint production (Silver production and the money supply in England and Wales, 1086–c. 1500).

Yet Allen argues that Devon silver was not the main source, especially during periods of great depression, or during the 'Great Bullion Famine' in the 1290s and the mid-15th century.

The Combe Martin Silver Mines

The Combe Martin Mine Tenement, situated at Bowhay Lane, Combe Martin, Ilfracombe EX34 0JN, is a prominent historic site of silver extraction dating back to the 13th century or even earlier (Combe Martin Silver Mines online). The mine tenement can be visited on certain days.

Silver from the Combe Martin mines was exploited for the Crown's war chest, during the Anglo-French Wars in the Middle Ages (White's Gazette, 1878). The produce was so considerable as to assist the Black Prince - Edward of Woodstock (1330 – 1376) - in The Hundred Years War.

Those same mines also yielded good amounts of silver under the Tudor monarchy; "their most productive period was the latter part of the sixteenth century onwards" (Devon and Dartmoor HER MDV12545).

Bere Ferrers and Bere Alston, Devon

Bere Ferrers, on the Bere Peninsula bordering Cornwall, contributed substantially to the silver output in England and Wales during the late medieval period (Archaeology, University of Exeter, 2023).

Mindat.org (2023) reports that the thirteenth-century mines at Bere Alston, Yelverton - a group of silver-lead mines in the civil parish of Bere Ferrers - are amongst the oldest workings in Britain.

According to the University of Exeter: the Bere Ferrers complex at the confluence of the rivers Tavy and Tamar in South Devon is a well-preserved example of medieval silver mining.

The Tamar Gawton Mine Complex

The University of Exeter’s Bere Ferrers Project has investigated the impact of these medieval mines on the historic landscape. Another significant complex is the Tamar Gawton Mine, a neglected national monument that has been "damaged by vehicles" (Historic England, 2023).

The Gawton Mine is a former copper and arsenic mine and processing complex, comprising a full range of buildings from cooperage to engine houses. It is located on the eastern banks of Devon's Tamar Valley (Devon and Dartmoor HER Number: MDV5490).

Evidence of Roman Mining Activity

In traditional silver mining, galena and jarosite extracted from mines was processed in nearby furnaces. Slag and sludge were deposited in heaps on site, which depending on the mining history is still found at some sites today including ancient structures (Hirt, Alfred M., 2020).

The Mendips Charterhouse Lead Mines, south of Bristol and Bath in Somerset, and the Deeside Pentre Ffwrndan Roman Settlement (Flintshire): are two known examples of Roman silver mining.

The Roman Army Legio II Augusta established a fortress at Exeter around AD55, and they remained there for about two decades. The city, known as Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter Royal Albert Memorial Museum information), was a significant Romano-British settlement (Exeter City Council, 2019).

In order to meet demand for consumables and lustrous metals in their empire: the Romans mined in Britain for a variety of ore deposits crucial to industry and trade.

Besides the noble metals gold, silver and copper: one of the most valuable metals was lead, used for plumbing and in Roman villas. Ore deposits could contain amounts of galena or zinc for making silverware, nickel and coinage.

Archaeological evidence suggests Roman mining activity near a fort discovered at the village of Calstock in south-east Cornwall during 2007 (BBC News, 2019; Ancient Origins, 2019). Calstock lies 12 miles upstream from Plymouth in an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

The Roman silver denarius coin, initially pure silver, was the linchpin of the Roman economy and the genesis of the Roman coinage system. To support those systems, the Romans sought and exploited argentiferous lead mines in Britain and elsewhere (Hirt, Alfred M., 2020).

Over time, the amount of silver in the standard denarius coin declined gradually along with the Roman empire; and then steeply to a negligible amount. It seems logical that the Romans shifted their silver mining activities to support their debased coinage, in their economy dependent on freshly-minted silver coins and bullion.

Calstock Roman Fort

The Calstock Roman fort was established around AD 50. It wasn’t unearthed until 2007, when a group headed by landscape archaeologist Dr. Chris Smart from Exeter University’s Department of Archaeology and History, conducted geophysical surveys of the region in search of medieval silver mining evidence (Merrington, A., June 2023).

Archaeological evidence indicating that the Roman army conducted metal mining operations in Cornwall, shortly after their invasion of Britain, was discovered and reported in 2023.

This significant discovery is thanks to research by archaeologist Dr Duckworth from the University of Exeter, in conjunction with the new series of Channel Four’s The Great British Dig.

Dr Duckworth reportedly analysed rocky material, found during excavations of odd-looking patches. A specialist portable x-ray fluorescence (pXRF) device was used. The material turned out to be Roman mining waste and the first excavated evidence that the Romans were mining for Cornwall’s mineral-rich deposits.

It's not explicitly stated that silver was mined at Calstock Fort during the Roman period, but a series of deep pits connected by arched tunnels, thought to be part of an ancient mine, were uncovered.

Further analysis was necessary to provide more insights into the scale and methods of Roman silver mining in Devon (Merrington, Exeter University News, 2023).

In conjunction with Combe Martin's history of metalliferous mining, and regional geological data: archaeological reports indicate that parts of Cornwall and Devon contained some of the richest mineral deposits in the world.

Mining for Lead in Ancient Britain

The British Geological Survey (2023) states that Lead mining has a long history, dating back to the Iron Age. However, the majority of mining activity occurred during specific time periods.

Notably, lead mining was prominent during the Roman occupation, as well as in the 17th and 18th centuries. This continued into the 19th century.

During these eras significant efforts were made to extract lead, in regions like the Mendip Hills and Derbyshire. The Romans, within six years of their arrival in Britain, were already engaged in mining activities.

Large ingots of lead from the Mendips have been discovered, some of which are now displayed in museums.

Later periods saw renewed mining efforts, technological advancements, and the use of Cornish mining techniques to explore deeper mines in search of richer ore deposits. Interestingly, in one mine, miners left their names imprinted in the mud, providing a glimpse into their lives and work.

At Charterhouse in the Mendip Hills: Henry Young and John Clark were working underground on 20th November 1753. The handwriting and the small size of finger marks suggest that some of the miners were children (BGS, 2023).

While recent isotopic analysis by Williams et al. (2025) has confirmed that British tin was reaching the Levant as early as the Bronze Age, the synthesis provided by J.P. for the Combe Martin Village History Project illustrates the enduring significance of these mineral deposits, tracing their extraction from the Iron Age through to their role as 'Royal Mines' in the medieval period,

Overall, lead mining has left a significant historical footprint across different epochs, reflecting both technological progress and the economic importance of this valuable resource.

© Author Harrison - 09 November 2023 | Revised on 19th December 2025.

Article attribution: Combe Martin Village History Project, 2023. Silver mining in Devon and Cornwall. Combe Martin Industrial History. Available at: https://www.combemartinvillage.co.uk/combe-martin-industrial-history/silver-mining-in-devon-and-cornwall [Accessed date...]

Sources and References Retrieved 28 October 2023 - 14 October 2025:

AOC Archaeology Group. (n.d. [2025]). What is a Hillfort? Retrieved from https://www.aocarchaeology.com/callanderslandscape/what-is-a-hillfort.

Allen, Martin (2010, 2011); Silver production and the money supply in England and Wales, 1086–c. 1500. The Economic History Review: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27919484.

BBC News (2019); Roman fort discovered under Cornwall’s streets. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cornwall-48841598.

British Geological Survey (2023): History of lead mining | Minerals and mines | Foundations of the Mendips (bgs.ac.uk)

British Geological Survey (1998): Minerals in Britain. Available at: https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/534495/1/mins_in_britain_leadzinc.pdf.

Combe Martin Silver Mines Society (CMSMS): https://www.combemartinmines.co.uk/contact/.

Claughton, P. and Smart, C. (2020): The Crown silver mines in Devon: capital, labour and landscape in the late medieval period.

Claughton, P. (2010): Journals, Open Edition; The Crown Silver Mines and The Historic Landscape in Devon (England). https://journals.openedition.org/archeosciences/2574.

Combe Martin Village History Project. (05. April 2023.) Early Silver Mining in Combe Martin / Combe Martin Industrial History. Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story]. [Online] Available at: https://www.combemartinvillage.co.uk/combe-martin-industrial-history/early-silver-mining-in-combe-martin (Accessed: November 2023).

Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site Management Plan 2020-2025; https://www.cornishmining.org.uk/media/Conservation/Management%20Plan/PDFs/Appendix_1-World_Heritage_Site_Area_Statements_A1-A10.pdf.

Cornish Mining World Heritage Site (2011): Devon Great Consols and the Tamar Valley Mining Heritage Project. Available online at: (2011) Devon Great Consols and the Tamar Valley Mining Heritage Project - Cornish Mining World Heritage Site.

Cunliffe, B. (1978) Iron Age Communities in Britain: An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC until the Roman Conquest. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Devon & Dartmoor HER (n.d.): HER Number: MDV12545. https://www.devon.gov.uk/historicenvironment/historic-environment-record-guidance/.

Exeter City Council (2019): Remains of Roman defences discovered under Exeter’s Bus Station site.

Exmoor National Park Historic Environment Records: https://www.exmoorher.co.uk/.

First excavated evidence of Roman metal mining in Cornwall found ; Newcastle University Press Office, June 2023.

Flynn, C.G., 1999. The decline and end of the lead mining industry in the Northern Pennines, England and Wales. PhD thesis, Durham University. Available at: https://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4569/.

Geology of Combe Martin: Geology of Combe Martin in North Devon / Combe Martin Landmarks | Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story].

Great Bullion Famine of the Fifteenth Century (The); Day, John (auth. 1978). https://www.jstor.org/stable/650246.

Harrison, JP; Combe Martin History Project (2023). Combe Martin Silver Mining. https://www.combemartinvillage.co.uk/combe-martin-industrial-history/early-silver-mining-in-combe-martin.

Heritage Gateway. "The Castle, Berrynarbor." Historic England Research Record Hob Uid: 34091.

Hirt, Alfred M. (2020); Gold and Silver Mining in the Roman Empire. Retrieved from https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3066254/3/Hirt%20Warwick%20Publ.%20III%20(revised).

Historic England (2023): Gawton Mine complex, Bere Ferrers / Gulworthy - West Devon. List Entry Number:1002667.

https://www.exeter.ac.uk/research/heritage/newsandevents/archaeology-cornwall-roman/.

Huge Hoard of Ancient Roman Silver Coins Worth £200,000 Found During Treasure Hunt. Retrieved from https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/roman-mine-0012234.

Jones, N.W., 2020. Roman settlement and industry along the Dee Estuary: recent discoveries at Pentre Ffwrndan, Flintshire. Archaeologia Cambrensis, 169, pp.127–163. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5284/1129098.

Markoe, G. (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press.

MDPI.com (2023): Silver Isotopes in Silver Suggest Phoenician Innovation in Metal Production.

Merrington, Andrew (June 2023): https://news.exeter.ac.uk/faculty-of-humanities-arts-and-social-sciences/great-british-dig-and-university-archaeologist-find-first-excavated-evidence-of-roman-mining-in-cornwall/.

Mindat.org. (n.d.). Galena: Mineral information, data and localities. https://www.mindat.org/min-1641.html.

Moore, John H. (n.d.): Roman Hele Bay, Ilfracombe, north Devon (johnhmoore.co.uk).

Northern Mine Research Society: Cornwall & Devon. Retrieved from https://www.nmrs.org.uk/mines-map/metal/cornwall-devon-mines/.

Prof. S. Rippon, Dr P. Claughton and Dr C. Smart (2009): Medieval silver mining in at Bere Ferrers, Devon. https://archaeology.exeter.ac.uk/research/projects/silvermining/.

Rondelez, P. & Claughton, P. (2013): Early silver mining in western Europe: an Irish perspective. https://www.academia.edu/7606260/Early_silver_mining_in_western_Europe_an_Irish_perspective.

Scottish Archaeological Research Framework, n.d. The Influence of Rome. Available at: https://scarf.scot/regional/pkarf/5-iron-age/5-6-the-influence-of-rome/. Accessed 14 October 2025.

Statista.com (2023): Mine production of silver worldwide from 2005 to 2022 (in metric tons).

Tylecote, R.F., 2009. Roman lead working in Britain. The British Journal for the History of Science, 2(1), pp. 25-43. doi:10.1017/S0007087400001825.

UNESCO World Heritage Convention (2023): Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1215/.

University of Exeter (n.d.): Archaeology: Cornwall’s Roman Fort. Retrieved from

University of Exeter. (n.d.). Silver Mining. Retrieved from https://humanities.exeter.ac.uk/archaeology/research/projects/silvermining/ .

Walls, T., 2000, A Prehistoric Defensive Enclosure in Berrynarbor, North Devon (Post-Graduate Thesis). SDV85968.

White's Gazette (1878-1879): https://www.combemartinvillage.co.uk/white-s-gazette-1878-1879.

Williams, R.A., Berger, D., Montesanto, M., Badreshany, K., Jones, A.M., Ponting, M., Aragón, E., Brügmann, G. & Roberts, B.W. (2025): From Land’s End to the Levant: did Britain’s tin sources transform the Bronze Age in Europe and the Mediterranean? | Antiquity, 99(405), pp. 708–726. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.41. Editorial.

![Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story] Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story]](https://primary.jwwb.nl/public/i/j/k/temp-bexcyixkrnloblaipglr/cmvhp-logo-01-june-2025-high.png?enable-io=true&enable=upscale&height=70)

![Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story] Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story]](https://primary.jwwb.nl/public/i/j/k/temp-bexcyixkrnloblaipglr/cmvhp-logo-01-june-2025-high.png?enable-io=true&width=100)