Modified on March 09, 2026

Copyright CMVHP 2026

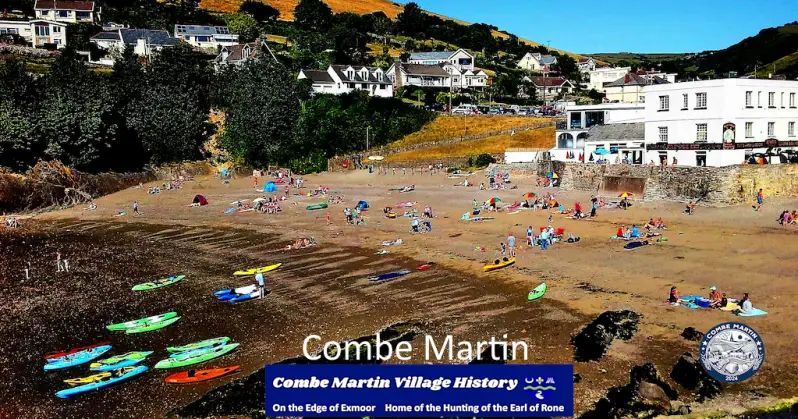

Combe Martin Village History Project

What's New

History Blog & Research Archive

Welcome to the CMVHP History Blog — part of a digital archive where research, community memory, and local heritage come together.

Here you’ll find original articles, downloadable studies, updates to our archive, and stories shared by residents and visitors.

From medieval landholding to silver mining, folklore, geology, and wartime life, these blog posts help bring Combe Martin’s history to life for everyone. Explore original research and free downloadable research articles (terms apply).

Our studies include referenced papers on the medieval descent and toponymy of Combe Martin.

Terms of Use: Restricted Non-Commercial Use | No Modifications.

CMVHP has taken care to ensure the accuracy of the historical information presented. However, some details may be subject to reinterpretation as new research emerges.

Our aim remains to make Combe Martin’s history available through transparent sourcing, careful writing, and open public access.

A Trusted Open Access Resource

Anonymous stats show a steady rise in visits to CMVHP, reflecting ongoing improvements to accessibility, structure, and content, as well as increasing community engagement with local history. The project is finding its returning audience.

The data suggests that visitors are not only arriving more often but staying to explore more pages per visit — a quiet sign that the archive is becoming a trusted local resource.

Free Downloadable Research Papers

Visitors are increasingly using CMVHP as a reference resource. On March 09, 2026, our project recorded 4,000 downloads of its free research papers in PDF format.

The download count is rising daily, reflecting sustained public interest in CMVHP's evidence‑based papers.

Terms of Use

All CMVHP publications and articles are released under copyright and a clear non‑commercial, no‑derivatives licence (no mixing). Our terms ensure that our archive remains freely accessible, while protecting our authors and the integrity of our research.

Also See: Combe Martin's Industrial History | Community Pages

This archive is scanned daily using SSLTrust & VirusTotal for malware and SSL integrity

Get Involved

The project welcomes historically relevant material from local residents or visitors. Personal recollections are also appreciated. Any items or recollections simply help strengthen the historical record for future generations.

If you wish to share relevant items or memories, please contact us↗; your privacy is respected. We are unable to accept business enquiries.

CMVHP Contributors

Every article on CMVHP is crafted by human contributors. No written content is generated by artificial intelligence (AI)—only knowledge, verified research, and word-processing by local residents. The website itself was created and is maintained by WeBmAsTeR.

Editors

- JP – Editorial architecture, citation systems, Privacy Policy

- WeBmAsTeR – Editorial lead, accessibility design

- Silverfox – Tudor legal history

- Shammickite Collective – Dialect preservation

- Redquill – Referencing, educator engagement

- Wicklow – Visual storytelling

Local Landmarks

- Molecatcher – Industrial heritage, silver mining

- Old Rope – Smuggling lore, maritime customs

- Cobbler’s Ghost – Cottage industries

- Lintel – Vernacular architecture

- Tallyman – Toll roads, market customs

Research & Skills

- Greenpete – Off-grid horticulture

- Strawbelle – Jam-making traditions

- The Fool – Festival customs, Earl of Rone

- Brackenwitch – Folk medicine, hedgerow lore

- Lanternjack – Nightwatch tales

Coding

- Bittern – Semantic markup, schema

- Loam – Responsive layout & Accessibility

- Kernelflint – Accessibility scripting

- Patchwire – Bug tracking, legacy browser support

Combe Martin’s dramatic cliffs doubled for California in a Hollywood film.

The Roses (2025), starring Benedict Cumberbatch and

Olivia Colman, was partly shot here.

Explore the film↗

Curious about terms like Owlers, adits, or Bideford Black? Visit our

Glossary of Combe Martin History

.

For exhibitions and visitor services, visit

Combe Martin Museum & Information Point

.

Downloadable Files Updated on March 09, 2026

Combe Martin’s mining story has gained an important new chapter with the release of our detailed 2026 retrospective analysis, covering the final decades of North Devon’s silver‑lead industry.

We have an academic research study on the ownership lineage, and seigniorial evolution, of the Manor of Combe Martin. Find our free downloads below, and on every page footer.

Our contributors also interrogate, and challenge, the genealogical embellishments that have accumulated around the figure popularly styled ‘Martin de Tours’.

License and Terms of Use: The CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license | © CMVHP 2023-2026.

Non-Commercial Use - No Modifications.

CMVHP has taken care to ensure the accuracy of the historical information presented. However, some details may be subject to reinterpretation as new research emerges.

CMVHP accepts no liability for any errors, omissions, or any use of this material. For enquiries regarding permissions, accessibility formats, or suggested corrections, please contact CMVHP directly.

Free Downloadable Research Papers © CMVHP 2026

Find these downloadable PDFs on our page footer menu ↓

Living History: Share Your Combe Martin Story

Send us your short Combe Martin history blog↗ and join the club.

Did you know that The Roses movie (2025) was partly shot in Combe Martin?

Read more at The Roses Filming Locations (2025) - A2Z Filming Location.

Everyone is welcome with parental guidance for younger contributors.

About Our Voluntary Work

Volunteers also conducted site visits to historic locations and cross-referenced oral histories with documented evidence. Combe Martin Museum proved an invaluable treasure trove, and our volunteers built the museum's new modern and accessible website.

Our voluntary team is currently developing a Glossary of Combe Martin, which acts as a quick-reference guide, helping readers understand terms like adits, Bideford Black, Shammickite, or Earl of Rone without needing to search through multiple articles.

The result is a growing digital archive that makes Combe Martin’s history accessible to everyone — from educators to researchers, visitors and local residents.

Changelog and Improvements

Our Changelog helps our collaborators and visitors to keep track of ongoing improvements and additions to this website. It also demonstrates our commitment to transparency, accessibility, and safeguarding.

CMVHP Blogs

Combe Martin History Blogs

Blog Posts for March 2026

Combe Martin’s mining story has gained an important new chapter with the release of our detailed 2026 retrospective analysis, covering the final decades of North Devon’s silver‑lead industry.

Find our study in PDF format, compiled by our researcher J.P., at our downloads section on this page.

We drew details from Burt, R., Waite, P., & Burnley, R. (1984). The Devon and Somerset Mines: Metalliferous and Associated Minerals, 1845-1913. University of Exeter. Published by A. Wheaton and Co. Ltd, Exeter. In association with The Northern Mine Research Society.

Credit belongs entirely to Burt, R., Waite, P., & Burnley, R. (1984), and The Northern Mines Research Society.

-

Drawing on production records, labour data, and global economic pressures, the study reveals how Combe Martin’s once‑rich argentiferous galena deposits entered a rapid decline between 1845 and 1913, culminating in the mines being formally listed as “not worked” by 1881.

-

This additional document helps bridge the gap between the village’s medieval silver boom and its Victorian industrial collapse, offering one of the clearest pictures yet of how global forces reshaped a small West Country mining community.

Blog Posts for February 2026

February 21, 2026.

Our CMVHP website is growing in real, organic terms.

Anonymous stats show a steady rise in visits to CMVHP, reflecting ongoing improvements to accessibility, structure, and content, as well as increasing community engagement with local history. The project is finding its returning audience, and the data suggests that visitors are not only arriving more often but staying to explore more pages per visit — a quiet sign that the archive is becoming a trusted local resource.

February 20, 2026.

Over the past year, the Combe Martin Village History Project has grown in ways we could never have imagined. What began as a community‑driven effort to preserve our parish’s stories has become a trusted local resource — and now, our work is being noticed in and beyond the village.

Local magazines and publications have recently approached us requesting permission to feature parts of our research, images, and historical articles. We’re delighted by this interest.

Blog Posts for January 2026

Updates to CMVHP V. 4.6.1.

25 - 27 January 2026

A Clearer, More Intuitive Homepage

The “Start Your Journey” cluster on the front page has been rebuilt from the ground up with:

-

larger, more accessible text

-

universal‑design colour modes

-

clearer navigation

-

a new “About the CMVHP Website” CTA button

-

improved icons and tooltips

-

external links opening safely in new tabs

The Start Your Journey cluster makes the archive easier to explore for all visitors — from casual readers to researchers and educators.

Our Site Improvements page now includes enhanced schema markup that describes its role as an accessibility and site‑improvement log. By structuring the version history, accessibility features, licensing information, and security updates in a machine‑readable format, we help search engines index the page more accurately.

We try to make CMVHP a well‑maintained, trustworthy educational resource. Continuous improvements support accessibility and UX. It also improves discovery and scoring, SEO, and long‑term preservation of the project’s work.

The FitzMartins and the Making of Combe Martin | © CMVHP Blog 08 January 2026

Our contributors investigated the early history of the Barony of Dartington and confirmed how its medieval lords — the FitzMartin family — gave Combe Martin its name. A team member produced a fully referenced research paper, available as a free download on this blog page (copyright, license, and terms apply).

What began as a single historical question expanded into a full study of the barony’s inheritance chain. Drawing on Domesday People (K.S.B. Keats‑Rohan, 1999), we traced the descent from William de Falesia to the FitzMartins, then to the Audleys, and ultimately the Crown. This sequence of ownership shaped the history of Combe Martin.

The paper follows the barony from its first recorded holder, William de Falesia, at the time of the Domesday Survey (1086), through its transfer to Robert FitzMartin, son of Martin de Tours. The FitzMartins became one of the major landholding families in Devon and Wales, and their long tenure at Dartington — and at the manor of Combe in North Devon — lasted for at least six generations.

It was during this period that the settlement came to be known as Combe Martin, meaning “the Combe belonging to the Martins.”

When the FitzMartin male line ended in 1324/5, their estates passed to their Audley relatives and later reverted to the Crown. The same inheritance path that governed Dartington also determined the descent of Combe Martin, leaving a lasting imprint on the village’s identity and name.

Discovering the Rocks of Combe Martin (Blog)

Did you know that the cliffs and rocks around Combe Martin are super old — even older than the dinosaurs? Millions of years ago, this whole area was under the sea. Layers of mud, sand, and tiny sea creatures slowly turned into the rocks we see today.

Read our accessible article on this subject: The Geology of Combe Martin in North Devon ↗

Some of these rocks were squashed, bent, and pushed around by huge forces inside the Earth. That’s why the cliffs look folded and wiggly in places. If you look closely, you might even spot fossils or shells trapped inside the stone.

People in Combe Martin used these rocks for all sorts of things — from building houses to mining silver deep underground. So when you walk along the beach or look up at the cliffs, you’re actually seeing the village’s ancient history right in front of you.

Exploring the rocks is like being a detective — the clues are everywhere if you know where to look.

Blog Posts December 2025

Popular Downloads

Combe Martin Manor: The Pollard Legacy PDF (on this page) has become one of the archive’s most accessed resources, with sustained download activity across schools, universities, and heritage groups.

We recently added The Manor of Combe [Martin] - Ownership & Lineage PDF to this blog page. It's a historical study of who controlled the Manor of Combe Martin from the Norman Conquest (1086).

December 2025 Feature

Pegasus Bridge, D‑Day 1944 - A Victory Forged in Training

This story was brought to us by Combe Martin locals, proud of their family members in one of the most famous events of World War II.

On the night of 6 June 1944, British airborne troops of the Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (Ox & Bucks LI) crash‑landed gliders beside Pegasus Bridge in Normandy. Within minutes, they seized the crossing intact, preventing German armour from threatening Sword Beach — one of the first Allied victories of D‑Day.

Among the troops was Sergeant Alfred Gordon Gooch, remembered for spearheading the assault with his comrades. Their courage is honoured today by the Veterans Charity, with a proposed memorial at Ilfracombe to commemorate both the march and the men who carried its spirit into Normandy.

This success was built on years of preparation, including the famous 135‑mile Ilfracombe‑to‑Bulford march in 1942, which forged stamina, discipline, and unity. Under Major John Howard’s leadership, the men’s speed and resilience turned surprise into triumph.

Victory at Pegasus Bridge was not only about endurance and courage — it relied on the gliders’ pinpoint accuracy, meticulous planning, and intelligence work that identified German defences.

The assault was reinforced by support from other units, including paratroopers and engineers. Support arms secured nearby bridges and elite units linked up from Sword Beach. Together, these elements ensured the strategic objective was captured intact and held against counter‑attack.

Legacy: Pegasus Bridge remains a symbol of planning, Intelligence, endurance, and leadership.

The Roses (Movie, 2025) and Combe Martin on Screen

Combe Martin’s cliffs and Exmoor’s coastal scenery recently stepped into the spotlight in the feature film The Roses. The Searchlight Pictures production captured the village’s seascape and natural drama — the same landscapes that have inspired folklore, writers, and generations of locals.

Just as Victorian authors once wove Combe Martin into their stories, The Roses now adds a cinematic chapter to the village’s heritage. Visitors can seek out the locations they’ve seen on screen, adding film tourism to the mix of history and literature that already draws people here.

The film reimagines The War of the Roses (1989), following a seemingly flawless couple whose relationship spirals into a bitter domestic standoff (See Filming Locations).

Combe Martin’s story keeps growing — from manors and mines to novels and now movies — all part of the village’s rich and evolving identity.

November 2025

Thomas Becket (c. 1119–1170) - Saint Thomas of Canterbury

Tracing the Legacy of Saint Thomas Becket in a Tudor Parish

Thomas à Becket (c. 1119–1170) also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, was chancellor of England and archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of King Henry II (r. 1154–89). See Canterbury Cathedral Learning↗.

Although he never visited Combe Martin, Becket's death as a church martyr in 1170, and his stand against royal control, had a lasting impact across England—even in small parishes like Combe Martin in North Devon.

In short: Combe Martin’s story intersects with Becket because its manor overlord, Sir Richard Pollard (1505-1542), was one of the men who literally carried out Henry VIII’s campaign to erase Becket’s legacy.

The Combe Martin Village History Project (CMVHP) explores how Becket’s defiance of royal authority helped shape the religious and political climate. It arguably transformed Combe Martin’s landholding, governance, and parish life.

Becket’s martyrdom and the Church vs. State Struggle: Becket’s assassination in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170 marked a turning point in English church-state relations.

Becket's refusal to subordinate ecclesiastical authority to King Henry II became a rallying point for defenders of the Church.

Following his canonisation in 1173, Becket’s cult of martyrdom elevated the symbolic prestige of parish churches, and strengthened clerical claims to spiritual authority throughout England

As noted by Frank Barlow in Thomas Becket (University of California Press, 1986), Becket’s legacy endured not only in liturgical reverence but in the ideological tension between the Crown and the church that persisted into the Tudor era.

Tudor Reforms and the Dissolution of the Monasteries: By the 1530s, Henry VIII’s break with Rome, and the ensuing Dissolution of the Monasteries, dismantled many of the institutions Becket had symbolised.

Sir Richard Pollard MP (1505-1542) Lord of Combe Martin Manor

For Combe Martin, Pollard’s notoriety ties the village into one of the most dramatic episodes of the English Reformation (c1527-1590). Pollard's role exemplifies how local gentry were drawn into national religious upheaval, and the Becket connection here is both symbolic and direct.

On 25 October 1537 the manor of Combe Martin was granted by King Henry VIII to Sir Richard Pollard, as the entry in the "Letters & Papers of King Henry VIII" records under "grants October 1537". The Combe Martin silver mines were reserved to the Crown—a direct outcome of the centralising reforms Becket had resisted.

Combe Martin Manor overlord Sir Richard Pollard MP was a legal agent of Thomas Cromwell, and one of the architects of the Dissolution. Pollard supervised the defacement of shrines including Thomas Becket’s, at Canterbury Cathedral, in September 1538.

This included the removal of relics, jewels, and bones, under royal orders to erase Becket’s cult and legacy. No authentic record confirms the ultimate fate of Becket's bones. His physical remains may have been burned, buried in secret or scattered across Europe.

Scholars such as Alec Ryrie, writing for institutions such as Christ Church University at Canterbury, highlight that the absence of evidence is itself the defining feature of the debate.

John Butler's The Relics of Thomas Becket (2000 [1995]), often associated with Canterbury Cathedral publications, directly and carefully sifts through the various pieces of evidence concerning the 1538 destruction.

In January 1888, during excavations in the eastern crypt of Canterbury Cathedral, workmen uncovered the skeletal remains of a tall, middle-aged man. The skull bore what appeared to be the mark of a sword blow.

Could these bones belong to St Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, slain within the Cathedral in December 1170 at the hands of King Henry II’s knights? (Butler, 1995, p. 45).

Butler weighs the probability of the bones being burned, secretly re-interred, or their identity being confused with other remains later exhumed in the crypt.

As G.W. Bernard argues in The King's Reformation (Yale University Press, 2005), the Dissolution was not merely a financial or political manoeuvre—it was a redefinition of ecclesiastical jurisdiction and local governance.

Combe Martin’s shift from feudal lordship to tenant-based landholding reflects this broader national upheaval.

Parish Continuity and Ecclesiastical Memory: Despite these reforms, Combe Martin’s Anglican parish church of St Peter ad Vincula retained its spiritual and architectural significance.

Combe Martin church’s dedication to “St Peter in Chains” evokes themes of captivity and liberation, resonant with Becket’s own struggle.

Combe Martin Church's 15th-century oak chancel screen, and Gothic structure, stand as testaments to the enduring ecclesiastical heritage that Becket’s martyrdom helped preserve.

CMVHP’s archival research, including references to Magna Britannia: Volume 6, Devonshire (Lysons & Lysons, 1822), documents Combe Martin’s evolution from a feudal manor to a community-led parish.

Takeaway:

Becket's Core Conflict: Becket died defending the principle of ecclesiastical autonomy (Church power) from royal authority (King's power). Combe Martin overlord Sir Richard Pollard was instrumental in the sacking of the martyr Thomas Becket's tomb.

Tudor Transformation: The Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII, which Sir Richard Pollard helped execute, was the final, total assertion of royal supremacy over the Church in England.

In short: Combe Martin’s story intersects with Becket because its overlord, Sir Richard Pollard, was one of the men who literally carried out Henry VIII’s campaign to erase Becket’s legacy.

Henry II’s actions backfired, immortalising Becket, while Henry VIII’s systematic destruction of shrines and relics effectively silenced Becket in English religious practice.

References

-

Duggan, A. (1980) Thomas Becket: A textual history of his letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Butler, J. (2020) The Relics of Thomas Becket: A true-life mystery. London: Pitkin, Batsford Books.

Blog Post: November 26, 2025

Improvements to the Combe Martin Events & Festivities Page

Tidied up the page format, headings and content. Updated the Combe Martin Events page↗.

Events are being added all the time - visitors are advised to check with the organisations listed on the page, for up-to-date information.

Added a dedicated online contacts list for Combe Martin organisations (e.g., Carnival, Earl of Rone Council, Museum, Village Hall, Women’s Institute, Gardening Club, Churches). Links added for convenience.

Blog Post: November 01, 2025

Site Design Tweaks: We spent some serious time today fixing the most frustrating part of web design: making the header look good on a big screen and mobiles. It's now cleaner and necessarily accessible.

It never ends - there's always something to fix, change or bin. We know that some text colours on this site are a bit iffy, and we promise we'll get to them.

We tweaked our mobile menu to make it more accessible and work better on phones and tablets.

For a content-rich site like ours, every detail matters, and we're also trialling a widescreen site format.

By extending our site backgrounds and featured images to the edges of the screen, the site design feels more modern, premium, and "cinematic". Hopefully our users now get a more immersive experience.

Blog Post: October 29, 2025

“I knew Mrs Parsons↗ when she lived in Combe Martin. She was a lovely lady, and I remember visiting Combe Martin Museum↗ with her more than once.” — from Shammickite 676 by email.

Posted with permission by CMVHP.

Blog Post: October 10 - 27, 2025

📱 Making the Site Easier for Everyone to Use

We’ve made a series of improvements to help all visitors—especially those using phones, screen readers, or assistive tools. You should see a smoother, clearer experience, though it's not all perfect yet.

-

We’ve launched a new Site Improvements section to keep you in the loop as we refine the Combe Martin Village History website.

-

From accessibility upgrades to mobile tweaks and editorial polish, we’re making the site easier to use for everyone—without taking it offline. You might see anomalies waiting to be fixed.

-

Dropdown menus now work better on phones and tablets - We fixed how they behave across different devices so they’re easier to open, read, and use—especially for mobile visitors.

-

Our contrast toggle is now fully accessible - Visitors who need high-contrast viewing (like those with low vision or light sensitivity) can switch modes easily, with clear labels and reliable performance across platforms.

-

Tooltips are now easier to see and hear - We improved how tooltips show up and how they’re read aloud by screen readers, so users on touchscreens or keyboards get the help they need without confusion.

-

Important buttons are now easier to find and tap - We moved and resized key buttons like the site index and glossary, to make them more visible and easier to use for everyone.

Blog Post: October 06, 2025

📰 The Shammick Chronicle - Launched in October 2025

From Feudal Manor to Coastal Heritage—Combe Martin’s Story Comes Alive

We’ve released the December 2025 edition of The Shammick Chronicle, our community’s new heritage newsletter that brings Combe Martin’s layered past into vivid focus.

This Christmas issue tells a story of transformation—from medieval landholding to modern coastal resilience. Read stories including the 2025 Hollywood movie that showcases Combe Martin's dramatic seascape.

🏰 Sir John Pollard: Reform, Redistribution, and Local Legacy

Our October Newsletter posted on this page dives into the life and legacy of Sir John Pollard, a Tudor reformer, whose legal work helped dismantle feudal land structures. His connection to Combe Martin offers a rare glimpse into how national upheaval reshaped local identity.

Blog Post: 30 September 2025

Silver Stories and Visitor Surges: What Our Stats Are Telling Us

We’ve been keeping a close eye on our visitor stats lately—and it’s safe to say Combe Martin’s industrial past is striking silver once again.

Over the past 30 days, our Early Silver Mining in Combe Martin page drew more visitors, making it the most explored history topic after the homepage itself.

That’s more than the Pack o’ Cards Inn page, more than our Earl of Rone article, and even more than our Combe Martin Festival listings. Clearly, the story of Combe Martin’s underground riches is captivating readers.

Other mining pages are also seeing a lift:

• Silver Mining in Devon and Cornwall

• Combe Martin Ores and Smelting

• Mining at Exmoor National Park

• Culm – Plant or Coal?

It’s fascinating to see how these technical and historical pages are resonating. Whether it’s curiosity about smelting techniques or the mystery of culm, our readers are digging deep.

If you’ve recently explored these pages, thank you! Your interest helps us shape what comes next. And if you haven’t yet, there’s a whole seam of stories waiting to be uncovered.

Checkpoint: v2.5.1 (28 September 2025)

We’ve made meaningful refinements to the Combe Martin Village History Project today:

-

Refined PDF section with historically precise Tudor framing

-

Improved glossary phrasing and symbolic manor transitions

-

Streamlined footer and download links with semantic clarity

-

Strengthened educational tone and accessibility polish

Blog Post: 24 September 2025

Today we’ve updated our feature on one of Combe Martin’s most iconic landmarks—the Pack o’ Cards Inn. This whimsical, architecturally unique tourist attraction has long captured the imagination of locals and visitors alike.

✨ What’s New?

-

Heritage Badge Added: We’ve introduced a bold new Heritage Landmark – Est. 1690s badge, styled after a British blue plaque, to highlight the inn’s cultural significance.

-

Improved Accessibility: The article now includes clearer formatting, mobile-friendly layout, and screen-reader support.

-

Expanded Historical Context: We’ve deepened the narrative around the inn’s role as “the focus of village life,” exploring its social, cultural, and community importance through the centuries.

📚 Explore the Update

Read the refreshed article, and discover how this eccentric inn became a cornerstone of local heritage and village life.

Blog Post: September 09, 2025

Combe Martin, North Devon, is known today for its peaceful charm and dramatic cliffs. Yet two centuries ago it was a different story.

Besides veins of silver ore, beneath the surface of this sleepy village lay a thriving underground smugglers' world.

Barrels rolled ashore under cover of darkness, secret tunnels and sunken lanes echoed with whispered deals.

Free-traders defied the Crown to become legends.

This isn’t just legend or myth—it’s a tapestry woven from archival records, folklore, and the people in a coastal town who kept their secrets well.

We didn’t just write our article on smuggling—we unearthed it.

The Combe Martin Village History Project spent months combing through customs logs, court records, local memoirs, and academic studies.

We bring you stories as rich as the illict spirits that once sloshed in hidden casks.

Blog Date: 08 September, 2025

The Golden Age of Smuggling

Picture the 18th century: Britain’s taxes on imported goods were sky-high.

Tea, tobacco, spirits—luxuries for some, necessities for many—were priced out of reach.

So the people of North Devon took matters into their own hands.

Combe Martin’s rugged coastline was a smuggler’s playground.

Hidden beaches, tidal caves, and winding paths made it nearly impossible for customs officers to keep up.

From Lundy Island to Watermouth Cove, the Bristol Channel became a highway for contraband.

In 1786, at Heddon’s Mouth just a few miles from Combe Martin, customs men seized 20 barrels of spirits and 13 bales of tobacco.

Yet that was a rare win, because most nights the smugglers won.

Caves, Kilns, and Clever Caches

The ingenuity of these free-traders was something to behold:

-

Caves at Lester Point and Samson’s Bay: Accessible only at low tide, perfect for stashing goods.

-

Napps Quarry tunnels: Discovered in the early 1900s, likely used for hiding contraband.

-

Lime kilns and graveyard tombs: Yes, even the dead played host to smuggled goods.

-

Floating barrels in rock pools: Hidden in plain sight, waiting for the right tide.

And let’s not forget the millers who weren’t just grinding grain for communities—they were part of the local network of trade, gossip, and sometimes smuggling.

Millers were trusted intermediaries who could quietly move goods under the radar, especially in tight-knit communities like Combe Martin.

As George Long wrote in The Mills of Man (1931), millers were key players—hiding goods beneath sacks of flour, passing them off to customers with a wink and a nod.

Folk Heroes or Criminals?

To the Crown, smugglers or freetraders were lawbreakers. To the locals, they were lifelines.

Take John Dovell of Combe Martin. In 1825, he was fined for hiding smuggled goods—a year’s wages gone in a flash.

John Dovell wasn’t just a smuggler; he was a wealthy and respected Combe Martin businessman and entrepreneur. A shipbuilder, and a pillar of the community.

John's grave and monument can be found on the north side of St. Peter ad Vincula Church graveyard.

It's a quiet yet fitting reminder of a man who walked both sides of the law.

Rudyard Kipling captured the mood best in A Smuggler’s Song:

“Watch the wall, my darling, while the Gentlemen go by.”

Published in 1906 as part of Kipling's story collection Puck of Pook’s Hill.

How We Researched Local Smuggling History

This isn’t folklore dressed up as fact. It’s a comprehensive study built from:

-

Customs records and court documents: Including the 1825 prosecution of Dovell and Low.

-

Academic sources: Bree Rosenberger, Richard Platt, and Robert Hesketh among others.

-

Local histories and oral tradition: Stories passed down, cross-checked, and preserved.

-

Site visits and geographic mapping: We walked the paths, studied the caves, and traced the routes.

Every detail has been verified, every tale grounded in evidence.

The Decline of Smuggling

By the mid-19th century, the tide turned. Tax reforms like the Commutation Act of 1784 made legal imports cheaper.

The risk no longer matched the reward. The smugglers faded into legend—but their footprints remain.

Walk the cliffs. Peer into the caves. You’re not just sightseeing—you’re tracing the echoes of a world that once thrived in the shadows.

Why This Story Still Echoes

Smuggling wasn’t just a crime—it was a culture. It shaped Combe Martin’s economy, its identity, and its folklore. By telling this story, we’re not just preserving the past—we’re breathing life into it.

For full references and further reading, visit the Combe Martin Village History Project : Smuggling archive↗

Owlers of North Devon: Smugglers in the Shadows

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, North Devon’s rugged coastline became a haven for Owlers—local smugglers who trafficked sheep, wool, brandy, tobacco, and other contraband.

The term “Owler” originally referred to a 'Night Owl' who illegally exported sheep, and English wool, to France. Yet Owling evolved to encompass broader smuggling activities.

France and the Low Countries had advanced weaving industries that craved English fleece. English Laws dating back to 1367 banned wool exports, to protect domestic manufacturers.

England had an abundance of wool but a struggling textile industry. English wool was one of the most valuable commodities in Europe, especially prized by textile manufacturers in France and the Low Countries.

Instead of encouraging trade, the British government imposed strict export bans to protect its fledgling domestic textile industry. That’s where the Owlers came in.

In this lucrative Black Market: Owlers, working under cover of darkness, could earn far more selling wool illegally to French merchants than through legal domestic channels.

Key features of Owler activity in North Devon:

Coastal Villages as Hubs: Places like Combe Martin, Ilfracombe, and Clovelly were ideal for smuggling due to their hidden coves and tight-knit communities.

-

Night Operations: Owlers often moved goods under moonlight, using small boats and secret paths to avoid customs officers.

-

Community Involvement: Smuggling was rarely a solo affair. Entire villages could be complicit, with local inns and farms serving as stash points.

-

Conflict with Authorities: The rise of the Coastguard in the early 19th century led to dramatic chases and occasional shootouts along the cliffs and beaches.

Owling wasn’t just about profit—it was also a form of resistance against high taxes and trade restrictions.

Reference:

Raven, Matt (2022). "Wool smuggling from England's eastern seaboard, c. 1337–45: An illicit economy in the late Middle Ages". The Economic History Review. 75 (4): 1182–1213. doi:10.1111/ehr.13141. ISSN 1468-0289.

In many ways, these smugglers became folk heroes, their exploits whispered in taverns and passed down through generations.

Delve into the captivating stories of our little parish with a big story! Our aim is to explore the history of Combe Martin, using the content available on this website to create engaging and informative blog posts.

Blogs for Everyone

Whether you're a local resident, a tourist visiting our beautiful village, or a history enthusiast eager to learn more, these blogs are tailored for you.

Our informative and conversational blogs make history accessible and enjoyable for everyone.

Engage and Share

Share our blogs on social media, and spread the word about Combe Martin's events and festivals.

Explore the stories of our village, and discover the little parish with a big story!

![Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story] Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story]](https://primary.jwwb.nl/public/i/j/k/temp-bexcyixkrnloblaipglr/cmvhp-logo-01-june-2025-high.png?enable-io=true&enable=upscale&height=70)

![Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story] Combe Martin Village History [The Little Parish with a Big Story]](https://primary.jwwb.nl/public/i/j/k/temp-bexcyixkrnloblaipglr/cmvhp-logo-01-june-2025-high.png?enable-io=true&width=100)

How it works: Clicking the blue Contribute banner will open your email client with a new message addressed to us. You can email us your comment or story directly for review by the Combe Martin Village History Project.

Privacy Notice: Your message will be reviewed by the editorial team and may be published on the site. We do not share contributor information with any third parties. By sending your message, you consent to its potential publication under our CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. You can review our full Privacy Policy for details.

Note: This method does not guarantee secure transmission. You are not obliged to supply your given name, and please avoid including sensitive personal information.

Note: Thanks for your comments which help the Combe Martin community and our heritage website.